题目内容

(请给出正确答案)

题目内容

(请给出正确答案)

What can cause the disasters of gap years?A.Intervention of parents.B.Careful planning.C.G

What can cause the disasters of gap years?

A.Intervention of parents.

B.Careful planning.

C.Good health.

D.Realistic expectation.

题目内容

(请给出正确答案)

题目内容

(请给出正确答案)

What can cause the disasters of gap years?

A.Intervention of parents.

B.Careful planning.

C.Good health.

D.Realistic expectation.

更多“What can cause the disasters o…”相关的问题

更多“What can cause the disasters o…”相关的问题

A、Binary search 二元搜索

B、Brute force search 蛮力搜索

C、Informed search 有信息搜索

D、Uninformed search 无信息搜索

E、Heuristic search 启发式搜索

A、Dose euthanasia reduce the burden of the family?

B、Does euthanasia respect the human rights of patients?

C、Can euthanasia save the medical and health resources?

D、Would euthanasia make the patient miss some potential opportunities of new treatment in the future?

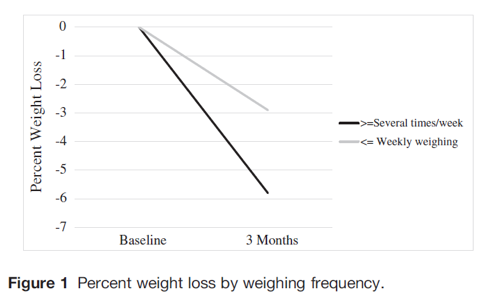

25-32. Read the following research paper and answer the questions. (Notes: The numbers in the brackets are in-text citations. References are omitted) Frequency of self-weighing and weight loss outcomes within a brief lifestyle intervention targeting emerging adults 1 Introduction More than 40% of 18–25 year old in the U.S. meet criteria for overweight or obesity, (1) placing them at increased cardiometabolic risk (2). This developmental period is associated with numerous life transitions (e.g. living independently, balancing work and school) as well as unhealthy weight-related behaviour (e.g. declines in physical activity, increased consumption of fast food, poor sleep) that contribute to weight gain and obesity during these years (3). Moreover, data indicate that this age group is all but absent from standard adult behavioural weight loss trials, representing less than 1% of enrolled participants (4). Researchers have called for programs targeting this unique transition from adolescence into early adulthood, (5) including those specific to weight loss (6). Our formative data suggest that to effectively engage this population, lifestyle interventions must be brief, with minimal in-person contact, content tailored specifically to 18–25 year old, and importantly, that programs must promote autonomy and allow for choice in behavioural goals (7,8). Thus, it remains a challenge how best to adapt evidence-based programs in a way that will appeal to this population and can produce clinically significant weight losses through such a low touch program while still affording participants choice surrounding behavioural goals as opposed to providing prescriptions. Frequent self-weighing may represent a simple self- regulation tool that can be used to promote clinically significant weight loss within a brief, reduced-intensity lifestyle intervention targeting emerging adults. In adults, frequent self-weighing has been associated with weight gain prevention, (9) weight loss (9–12) and weight loss maintenance (12–14) and is not associated with unhealthy weight control practices or worsening of psycho- logical symptoms (11,15,16). Less is known about the effects of frequent self-weighing among young adults; some studies have reported associations between self- weighing and negative psychological symptoms (17), while others indicate that frequent self-weighing might be part of a constellation of healthy weight-related behaviour (18). Importantly, data suggest that within the context of a lifestyle intervention targeting young adults 21–35 years of age, frequent self-weighing was not associated with increased depressive symptoms, disordered eating or body satisfaction and was associated with better weight loss (19) Further, several studies have examined self-weighing within the context of weight gain prevention efforts targeting first year college students (20–23); and data indicate high adherence and accept- ability of self-weighing (22). Impact on prevention of weight gain has been mixed with some studies reporting benefits of daily self-weighing within minimal weight gain prevention interventions (20,23), while others have noted benefits only within the context of a more comprehensive online healthy lifestyle program (21). In these studies, frequent self-weighing has not been associated with adverse psychological outcomes (21,22). Of note, these previous studies were conducted within the context of weight gain prevention and focused exclusively on college students. To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the relationship between frequent self-weighing and weight loss in a behavioural weight loss program targeting a broader sample of emerging adults. Thus, the primary aim of this paper is to examine the frequency of self-weighing among a racially diverse sample of emerging adults between 18 and 25 years enrolled in a brief lifestyle intervention, and to examine the association between frequent self-weighing and weight loss. 2 Methods 2.1 Intervention description These secondary analyses were conducted using data from a 3-month behavioural lifestyle intervention, SPARK RVA. The primary findings have been reported elsewhere (15), but in short, the aim of the original study was to examine the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of three approaches to promote engagement and weight loss in this age group. Mode of delivery differed: face-to-face, web and hybrid (web lessons plus optional in-person classes), as did the relative emphasis on promoting autonomy. Across all arms, evidence of the benefits of regular self-weighing was presented to participants, but explicit self-weighing prescriptions were not provided. Instead, participants were encouraged to weigh themselves at least weekly and no more than once per day, but were allowed to choose their own target. 2.2 Recruitment and participants SPARK RVA was advertised via web and print advertisements, radio spots and email blasts throughout the Richmond, VA area. Interested individuals were directed to a study recruitment website, where they could review study details and if interested, were able to complete a secure survey in order to determine eligibility. Inclusion criteria were ages 18–25 and BMI 25–45 kg/m; exclusion criteria were physical or mental health conditions that pose a safety concern or are associated with unintentional weight change, recent (i.e. within the past 6 months) pregnancy and recent >5% weight loss. Participants (N = 52) were mostly female (79%), and the sample was diverse (54% racial/ethnic minority) with a mean age of 22.3 (2.0) and mean BMI of 34.2 (5.4). 2.3 Measures Anthropometrics Measures of weight (kg) and height (cm) were taken by masked research assistants using standard protocols at baseline and post-treatment (3 months). Frequency of self-weighing At all assessment points, participants responded to the following question: ‘During the past month, how often did you weigh yourself?’ Response options are (i) several times a day; (ii) once a day; (iii) several times a week; (iv) once a week; (v) less than once a week; (vi) less than once a month; and (vii) never. 2.4 Statistical analyses Data were collapsed across treatment arms and con- ducted with completers (retention > 80%). There were no baseline differences on weighing frequency for those participants who were retained vs. not. Generalized linear modeling was used to examine change in frequency of self-weighing over time as well as to compare weight loss at post-treatment for those who reported frequent self-weighing (i.e. several times per week or more) vs. those who reported weighing less frequently (once a week or less). Subsequent analyses were conducted in which participants were categorized according to their change in weighing frequency from baseline to 3 months (i.e. increasers, stable and decreasers). Chi-square analyses were conducted to examine categorical variables (e.g. achieving a 5% weight loss). Treatment arm, gender and race were included as covariates in all analyses; those analyses examining weight change in kilogram also included baseline weight as a covariate. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22. 3 Results At baseline, a majority of participants (64.5%) reported self-weighing less than once a week, with only 15.4% weighing once per week and 21.1% reporting frequent self-weighing defined as at least several times per week. Self-weighing increased over the 3-month treatment program (p < 0.001); at post-treatment only 19% of participants reported self-weighing less than once per week, whereas 42.9% of participants reported self-weighing weekly and 38.2% of participants reported self-weighing several times per week or more (Table 1). Increase in frequency of self-weighing from baseline to post-treatment was associated with greater weight loss (β =-0.433, t = -3.02 and p = 0.01). Further, participants who reported frequent self-weighing (i.e. several time per week or more) at post-treatment achieved greater weight losses than those weighing weekly or less (p = 0.03, Figure 1). In addition, participants who endorsed frequent self- weighing were more likely to achieve a clinically significant (i.e. 5% of baseline weight) weight loss (p = 0.01). Finally, when participants were grouped according to change in weighing frequency (increasers, stable and decreasers), those who increased their frequency of self-weighing experienced the greatest weight loss relative to those who remained at the same frequency of weighing or decreased frequency of weighing, although this effect only approached statistical significance (—4.9+ 4.2 kg, —2.3 + 3.5 kg, and —0.92 + 2.2 kg, p = 0.06).

4 Discussion In a brief lifestyle intervention specifically designed for 18–25 year old with overweight or obesity, frequent self- weighing was associated with greater weight loss at post-treatment. These results are consistent with findings among other adults (9–12) and suggest that frequent self- weighing may be an important factor in weight control among this population as well. Of note, no prescriptions were given in the current study – rather, consistent with our formative data, evidence was presented about the benefits of self-weighing and participants were allowed to select the target they felt was best suited for them in order to promote autonomy. In light of the current findings and previous data demonstrating the benefits of more frequent self-weighing (9–14), future studies should consider providing this population with a forced choice between frequent self-weighing (i.e. >several times per week) and daily self-weighing to promote optimal weight management while still allowing for choice in behavioural targets. Indeed, frequent self-weighing might be a particularly valuable self-regulation tool for this age group given evidence to suggest dietary self-monitoring is a substantial challenge in this population (8); thus, the scale serving as an error detector might serve to enhance overall self- regulation of energy balance behaviour and weight loss in this high-risk age group. Limitations of this secondary analysis include a limited sample size, lack of an assessment of psychological variables such as depression and disordered eating, and collapsing across treatment arms; further, within the trial from which these data are drawn, participants were not randomized to different self-weighing prescriptions, limiting the inferences that can be drawn regarding causality. Of note, many previous studies have demonstrated a lack of adverse psychological outcomes associated with frequent self-weighing in adults (11,15,16), as well as first-year college students (22) and a broader sample of young adults (19); nevertheless, future studies should explore the effects of frequent self-weighing on psychological variables including depressive symptoms and disordered eating within the context of a weight loss intervention targeting this specific age group. Strengths of the current study include a diverse sample including 54% racial/ethnic minorities, and the fact that this is the first study to examine the relationship between self-weighing and weight loss within a sample of treatment-seeking, overweight/obese 18–25 years old. Findings suggest that frequent self-weighing is associated with better weight loss outcomes among a racially diverse same of 18–25 years old enrolled in a brief lifestyle intervention. References (Omitted) 25. What is the topic of the research?

4 Discussion In a brief lifestyle intervention specifically designed for 18–25 year old with overweight or obesity, frequent self- weighing was associated with greater weight loss at post-treatment. These results are consistent with findings among other adults (9–12) and suggest that frequent self- weighing may be an important factor in weight control among this population as well. Of note, no prescriptions were given in the current study – rather, consistent with our formative data, evidence was presented about the benefits of self-weighing and participants were allowed to select the target they felt was best suited for them in order to promote autonomy. In light of the current findings and previous data demonstrating the benefits of more frequent self-weighing (9–14), future studies should consider providing this population with a forced choice between frequent self-weighing (i.e. >several times per week) and daily self-weighing to promote optimal weight management while still allowing for choice in behavioural targets. Indeed, frequent self-weighing might be a particularly valuable self-regulation tool for this age group given evidence to suggest dietary self-monitoring is a substantial challenge in this population (8); thus, the scale serving as an error detector might serve to enhance overall self- regulation of energy balance behaviour and weight loss in this high-risk age group. Limitations of this secondary analysis include a limited sample size, lack of an assessment of psychological variables such as depression and disordered eating, and collapsing across treatment arms; further, within the trial from which these data are drawn, participants were not randomized to different self-weighing prescriptions, limiting the inferences that can be drawn regarding causality. Of note, many previous studies have demonstrated a lack of adverse psychological outcomes associated with frequent self-weighing in adults (11,15,16), as well as first-year college students (22) and a broader sample of young adults (19); nevertheless, future studies should explore the effects of frequent self-weighing on psychological variables including depressive symptoms and disordered eating within the context of a weight loss intervention targeting this specific age group. Strengths of the current study include a diverse sample including 54% racial/ethnic minorities, and the fact that this is the first study to examine the relationship between self-weighing and weight loss within a sample of treatment-seeking, overweight/obese 18–25 years old. Findings suggest that frequent self-weighing is associated with better weight loss outcomes among a racially diverse same of 18–25 years old enrolled in a brief lifestyle intervention. References (Omitted) 25. What is the topic of the research?

A、Relationship between frequency of self-weighing and weight loss

B、A brief lifestyle intervention targeting emerging adults

C、Criteria for overweight or obesity

D、Unhealthy weight-related behaviour

A、To examine the frequency of self-weighing among a racially diverse sample of emerging adults and the association between frequent self-weighing and weight loss.

B、To call for programs targeting this unique transition from adolescence into early adulthood, including those specific to weight loss.

C、To promote autonomy and allow for choice in behavioural goals.

D、To adapt evidence-based programs in a way that will appeal to this population and can produce clinically significant weight losses through such a low touch program.

A、2-4-1-5-3

B、1-4-3-2-5

C、4-2-5-1-3

D、3-2-5-1-4

A、Frequent self- weighing was associated with greater weight loss at post-treatment.

B、These results are consistent with findings among other adults.

C、Frequent self- weighing is related with weight control among this population.

D、Frequent self-weighing might be a particularly valuable self-regulation tool for this age group.

A、Increase in frequency of self-weighing was associated with greater weight loss.

B、Those who decreased their frequency of self-weighing experienced the greatest weight loss.

C、Those who endorsed frequent self- weighing were more likely to achieve a significant weight loss.

D、Those who reported frequent self-weighing at post-treatment achieved greater weight losses.

A、The sample size is small.

B、There is a lack of an assessment of psychological variables.

C、Participants were not randomized to different self-weighing prescriptions.

D、There is a diverse sample including 54% racial/ethnic minorities.

为了保护您的账号安全,请在“简答题”公众号进行验证,点击“官网服务”-“账号验证”后输入验证码“”完成验证,验证成功后方可继续查看答案!

微信搜一搜

微信搜一搜

简答题

简答题

微信搜一搜

微信搜一搜

简答题

简答题